Bags, Boxes, and the Hidden Cost of Treating All Good Practices the Same

In my previous newsletter, I introduced a simple principle to decide if a good practice should be standardized in an organization:

“Who will notice if a team doesn’t follow this rule?”

This question alone can make your operating systems simpler and cleaner. But asking it is just the first step - what you need is an operating mechanism to act on the answer. I call it “Bags and Boxes”. It’s a mix of good practices, processes, and even incentives that shape how people behave inside your organization, explicitly or not.

Now, I know what you're thinking.

“How are bags and boxes going to help solve the chaos in my org?”

Let me show you.

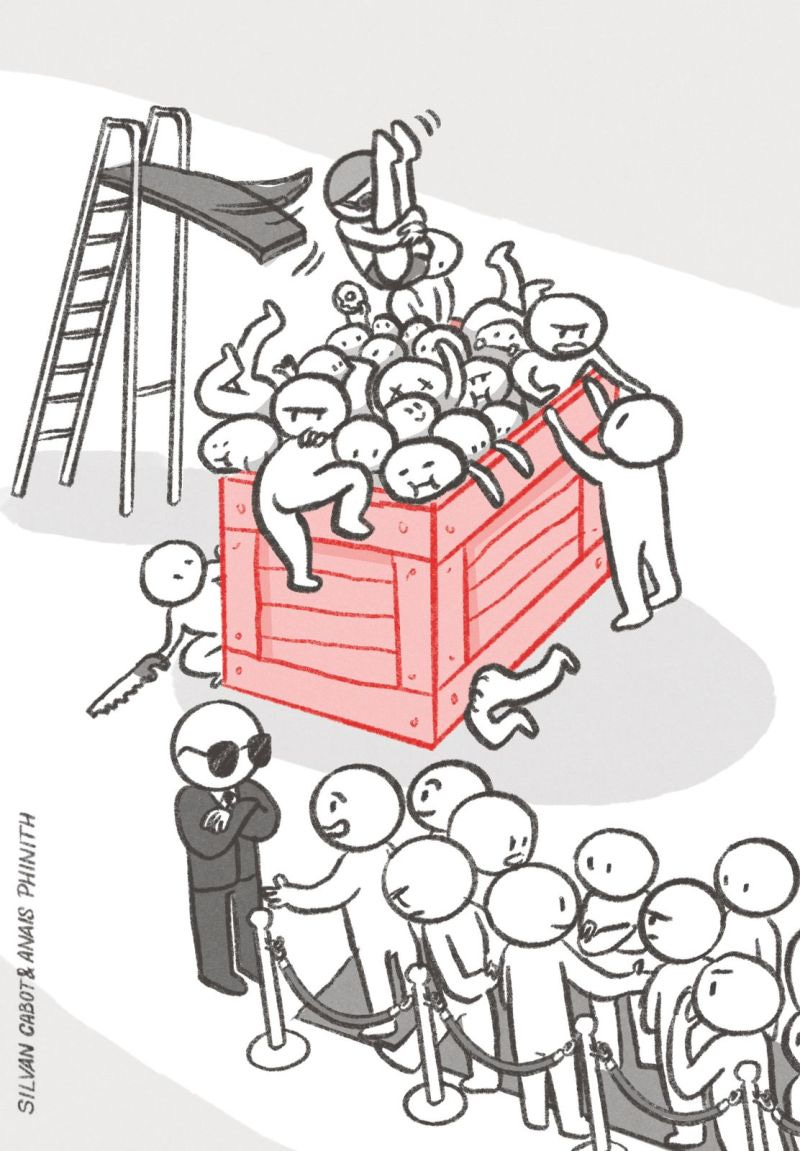

The Danger of Mixing Bags and Boxes

When you don’t separate mandatory good practices from optional ones, everything becomes mandatory.

Every new process someone introduces? Mandatory.

Every best practice from a blog post? Mandatory.

Every checklist someone swears by? You guessed: mandatory.

Why? Because we only know how to manage mandatory best practices.

We write them down, train people on them, measure compliance. Easy.

But when it comes to non-mandatory ones, most companies don’t have a clue. They don’t get tracked. They don’t get shared. They’re invisible to the system.

So what happens? We make them mandatory, because that’s the only way we know how to deal with them.

But the moment you force standardization on everything, you overload your teams, and your culture. What started as a well-meaning effort to align everyone turns into a slow drift toward bureaucracy that is nothing more than shooting yourself in the foot. Repeatedly.

And the more mandatory processes you have, the worse they work.

The solution? Stop standardizing every process. Because not everything deserves to be a box.

Boxes: Necessary, but Rigid and Expensive

Boxes are solid. Not by accident, but by design, built to protect what’s inside.

In your organization, boxes are the good practices you must standardize because they feed other teams and processes. Think: deployment protocols, planning templates, delivery formats, shared definitions.

When a team skips a boxed practice, someone else ends up paying the price. Usually in translation costs, poor handoffs, or worse: broken trust between teams.

Boxes can be mass produced and duplicated. Their strength is their consistency: one kind of box looks exactly the same across the organization.

Boxes are owned by leadership and they’re top-down mechanisms, inflexible by design. Every team gets the same box, and that’s the whole point. Because when a good practice goes in a box, you want predictability. You want to know when and how it’s used, and what it will produce. That’s what makes it safe to share it across teams.

And yes, they work. But they come at a cost.

Boxes require design, discussion, trade-offs. You need alignment, documentation, and discipline to make them work. They’re expensive to build, and to maintain.

Not everything should be put inside a box. Some good practices are better put in bags.

Bags: Flexible, Local, and Underappreciated

On the contrary, bags are very flexible.

They change shape, adapt to their contents, and evolve with use. You can squash them, stretch them, even put bags inside other bags. It doesn’t matter if it gets messy.

In your organization, bags hold the good practices that don't need standardization. They're still valuable tools, just not mandatory ones. Think: team rituals, productivity hacks, or even backlog structure.

What makes something a bag? Its output doesn't directly affect other teams.

You can modify it, replace it, or even discard it when it no longer serves you. And that flexibility is precisely the point.

Each team carries their own unique bag collection. Some go all in on polished methods (the luxury tote version). They might invest in expensive tools, or dedicated coaches to make it work. Others carry paper bags: quick, cheap and good enough. Some test different bags for the same good practice until they find one that works. And yes, trends come and go (remember waistbags?)

You don’t need to monitor these practices. Their performance has no cross-team impact, so enforcing or tracking them adds no real value.

But they should be lightly documented. Not to control them, but to let others reuse and remix them.

There’s only one rule: no bag can contradict a box.

Why This Works (And Why Most Orgs Screw It Up)

We are great at managing boxes - think about the amount of books written about process governance. But bags? Nobody talks about them. So we treat them like unfinished boxes, or worse, like something to get rid of. This leads to a predictable cycle:

Someone introduces a new practice

Nobody asks whether it’s a box or a bag

It quietly becomes a rule

But it was never meant to be a rule. So no one enforces it, and no one follows it either. It just sits there, half-dead in the middle of your org. Your teams stop trusting the process and engaging with any of it.

That’s the real cost of ignoring bags.

And ironically, this is exactly what weakens your boxes. When everything is a box, nothing really is. It’s bags that make the system hold. They give teams the freedom to experiment, to learn, to adapt. And in doing so, they protect the legitimacy of the mandatory practices.

If you want your boxes to hold, you must protect your bags.

That means:

Letting teams own them

Making space to share and improve them

Creating rituals to surface them

Making sure newcomers can find and learn from them

Encouraging teams to be curious about each other’s bags

Reminding people that not everything needs to be enforced

Most companies obsess over the quality of their boxes. The smart ones invest just as much in their bags.

My next newsletter will be entirely dedicated to bags. I will tell you how to implement and communicate them, and describe the anti-patterns I see the most around this topic.